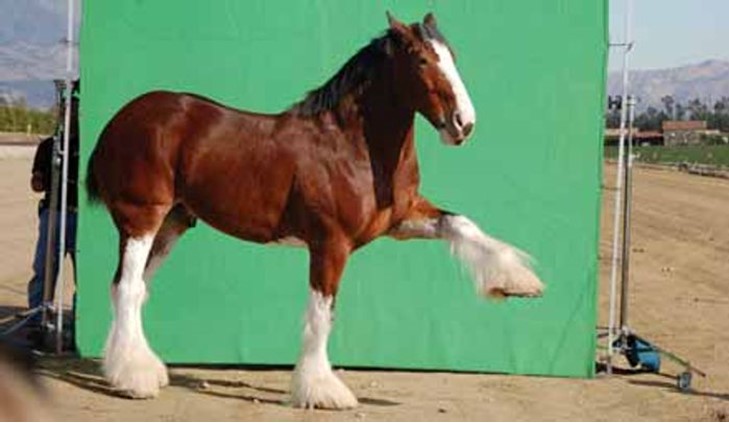

They are pampered to the max, never travel coach and demand 60 pounds of hay a day. But advertising directors are dying to work with them.

“I’ve had actors that are more trouble,” says Greg Popp, a commercial director for the famous Budweiser Clydesdale horses.

The eminent equines,which appeared in a Sunday Super Bowl ad, are fan favorites who’ve starred in nearly 50 commercials for the Anheuser-Busch brewer.

Less known is their reputation as perhaps the most consummate professionals on the advertising circuit. Industry veterans who shoot commercials consider working with the horses a career pinnacle, like a movie director who finally gets to direct Meryl Streep.

Clydesdale scuttlebutt includes remarkably few tales of horseplay or haughty hoof stomping. They arrive on time, take direction, and rarely miss their mark. “They are less like child actors and more like famous athletes,” says Michael Aimette, the chief creative officer at the advertising agency FCB New York, which worked on this year’s Super Bowl spot

The ad showed the Clydesdales coming to the rescue when a snowstorm kept a beer delivery truck from reaching a small town. The sturdy horses heroically pulled the beer in. Their journey to the Super Bowl screen began this past October, when executives at FCB had just wrapped their pitch presentation. Anheuser-Busch’s chief commercial officer Kyle Norrington slammed his hand on the table and said, “We’ve got something good here. Let’s get Robin on the line.”

“Robin’s a genius”

Thus began a well-oiled chain of events to turn a storyboard in Manhattan into a 30-second film of equine prowess watched by millions of people. Directors are called, ad space is bought—and on a ranch about 70 miles east of Jackson, Wyo., horse trainer Robin Wiltshire gets a call.

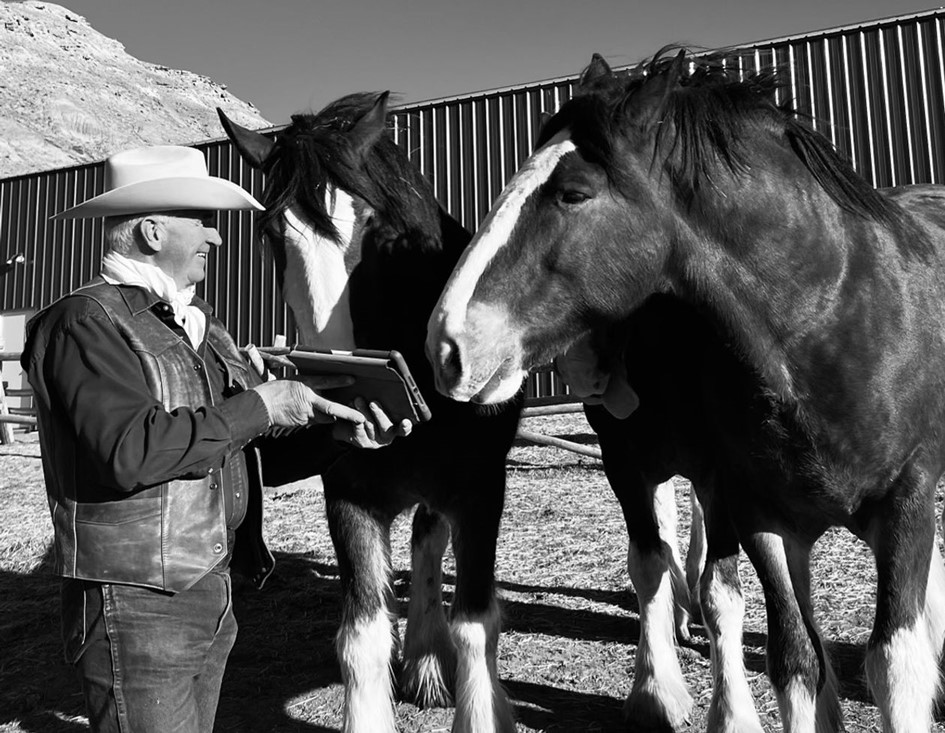

Wiltshire, a 60-plus Australian who was drawn across the world by the romance of Hollywood’s Old Wild West, is the man responsible for turning this herd into stars. He’s worked with Budweiser more than 25 years.

“Robin’s a genius,” says Zack Snyder, the Hollywood auteur behind films ”Justice League” and “Dawn of the Dead,” who early in his career directed ads for Budweiser through the production company Believe Media.

“You’ll be saying, ‘OK I want them to walk up, line up, and stop and look at each other,’ but you’ll be thinking, ‘How are they going to be able to do that?’ And he’ll say, ‘Oh yeah, sure.’” “And sure enough,” Snyder adds, “on the day they just do what they were asked.”

Praise helps

Here’s how it usually works: The ad agency sends the script and storyboard to Wiltshire, who works with Budweiser Clydesdale Operations to calculate how many horses are required. The chosen Clydesdales travel to Wiltshire’s Wyoming ranch via 65-foot custom horse trailers designed for their comfort.

Once training begins, the key, Wiltshire says, is to “make sure I’m there for feedings, and greet them morning and night, so they know my voice.”

It is similar to school, he says. Each Clydesdale must first learn to go to a mark with confidence before he adds the “horse actions” required to develop the story. Wiltshire relies on sounds, praise and preparation to get the horses to act. “When they really perform I stand and give them a big applause,” he says. “They really pick up on happy faces.” Wiltshire’s skills combined with special effects mean directors often aren’t constrained by what the Clydesdales can do naturally. In the world of advertising they can dodge “streaking” sheep and play fetch with a giant log. Yet, “you don’t want them to become too cartoony,” says John Hayes, another creative director who worked on Clydesdale ads. “Other animals can be goofy. The Clydesdales have to be majestic.”

Cameras occasionally have been sacrificed, such as in the shoot for the popular 1996 Super Bowl “Football” spot that showed the horses playing football. A Clydesdale was tasked with using its front leg to hike a ball. On hand was Conrad Hall, the late Academy Award-winning cinematographer who was director of photography for the production. Let’s just say Hall became part of the action. “My horse hikes the ball, it hits the lens in the camera, bowls Conrad completely over and he says ‘I got it!’” Wiltshire recalls.

Among the most difficult commercials to make was “Respect,” which followed a hitch of Clydesdales from snowy farmland through small towns and over the Brooklyn Bridge to pause and kneel before a lower Manhattan decimated by the 9/11 terrorist attacks just five months earlier. Wiltshire had to train the Clydesdales to bow their heads in unison, and the task began in New England in winter. “It would rain and my hat would turn to ice,” he recalls.

In the prep for this year’s Super Bowl ad, Wiltshire had Simon the Clydesdale practice the trick of knocking a hat off someone’s head with a multitude of headwear, as the producers hadn’t yet confirmed the type of hat the horse would be presented with.

Once ready, the Clydesdales and their entourage head to the set, and then the mane stars go to the spa—or rather, the spa goes to them. On average it will take a team of seven people up to five hours to wash and groom the horses, according to Budweiser Clydesdale handler Chris Wiegert. “I walked past once and one of the handlers was clipping their nose hairs,” says director Joe Pytka. “That’s how looked-after they are.”

Pytka, who directed the movie “Space Jam,”has directed at least eight Budweiser Clydesdale ads. Famous for his imposing stature, long white hair and booming voice, Pytka softened when it came to Wiltshire and the horses, say people who worked with them on set. “I never needed more than one or two takes,” Pytka says of working with the Clydesdales. “Frankly, it was painless.”

The Wall Street Journal. Write to Katie Deighton at katie.deighton@wsj.com

Suzanne Vranica contributed to this article.