As anyone who has spent real time with horses knows, they are so often the teachers in this journey through life. “As we strive to learn the best ways to motivate our horses, they motivate us to be the best that we can be,” says retired movie stunt rider and double, Martha Crawford-Cantarini.

“Horses were the unsung heroes of the era,” says Crawford-Cantarini, who started her career in 1947 at age 18. “They provided the action, the pacing and the indelible identity of the Western. Their ability to jump, to fall, and to run contributed hugely to a star’s believability and status.”

“One time I had to do a ‘chase’ scene with a team in St. George, Utah,” she says. “The head wrangler came early and located a local team of horses for me to drive. I was a bit spooked at the thought as it was an almost runaway scene. But the horses were wonderful, and I did not even need a pickup man to help me get stopped. The wranglers were wonderful, too. Each of them usually worked for a certain stable and knew each horse inside and out as to what it could do or not do.”

Crawford-Cantarini describes movie stunt horses as pleasing and mellow, with a kind eye, and says most of the best horses in the movies were mixed breeds. Photo courtesy of Martha Crawford-Cantarini.

In a century of film-making since the grainy black-and-white days of the 1920s, animals and especially horses have been part of the production scene. Without horses there would have been no classics such as National Velvet, Ben-Hur, The Big Country, Yellowstone Kelly, Son of Paleface, The Black Stallion, Seabiscuit, and War Horse, or timeless TV Western series like The Lone Ranger, Wagon Train, Gunsmoke, Bonanza, Maverick, The Virginian, or Cheyenne.

Above: In a promotional clip for The Big Country (1958), in which stunt rider Crawford-Cantarini doubled both Jean Simmons and Carroll Baker, she jumped a wagon and her horse, Jim, caught his foot behind the wagon wheel. She stepped off Jim’s back in mid-air and pulled him toward her, saving his leg. Jim went on to double Flicka in the well-known television series.

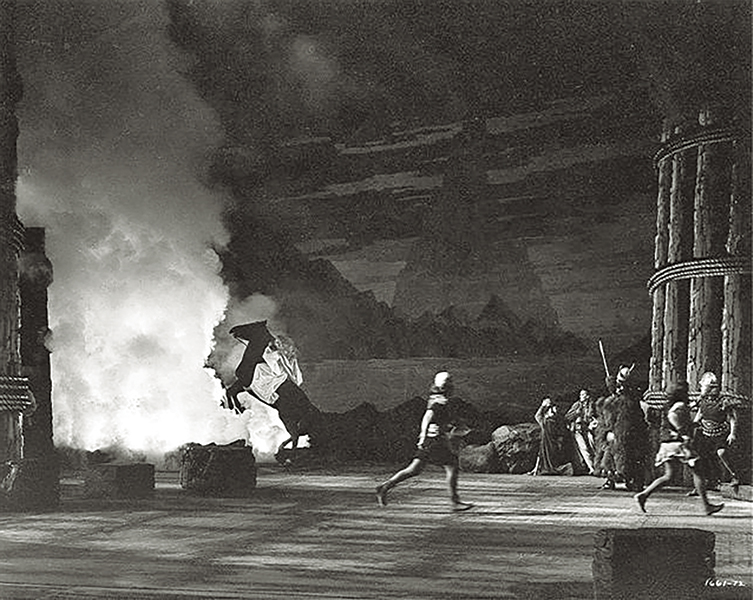

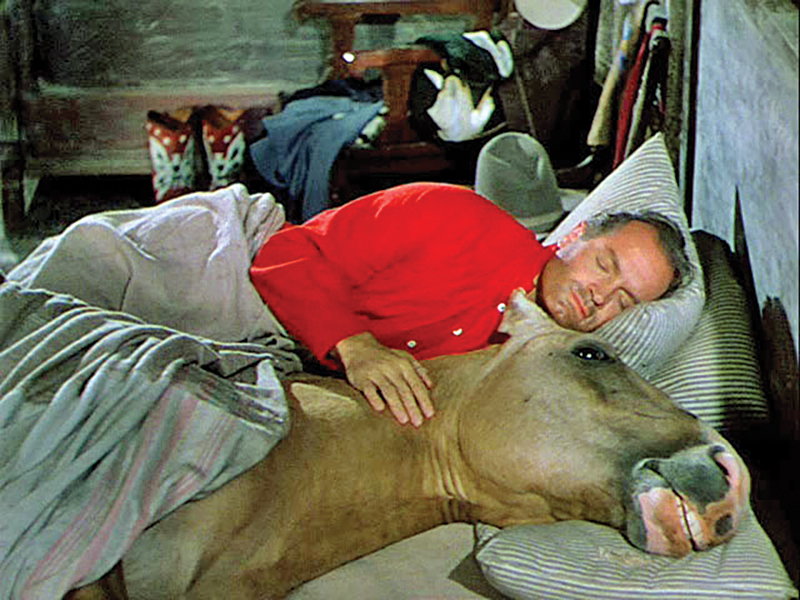

Below: In the fire scene in MGM’s Interrupted Melody (1954), Crawford-Cantarini’s horse, Ski, had to rear in front of the smoke and flames, then leap into the fire as Martha swung onto his back to a musical cue in a two-second time frame. Anticipating the action, the horse listened to the music, and braced himself with his left hind foot exactly one beat before the moment in the music when Crawford-Cantarini had to mount. Photos courtesy of Martha Crawford-Cantarini

“One time on a Cheyenne shoot, I was supposed to be in a daze and walk out in front of a runaway horse who knocks me down and kills me,” Crawford-Cantarini recalls. “Well, time and time again we did it and it would not work. So, risking my job, I told the director that a horse is not going to run into you unless he is running from fright. He will avoid you. I said to let me step into his shoulder with my arm as he goes by me and I will fall back. It will look like I was run over if you put the camera on the other side. Much to my surprise, he said okay and we got it the first try. Clint Walker thanked me for the great job. That was nice.”

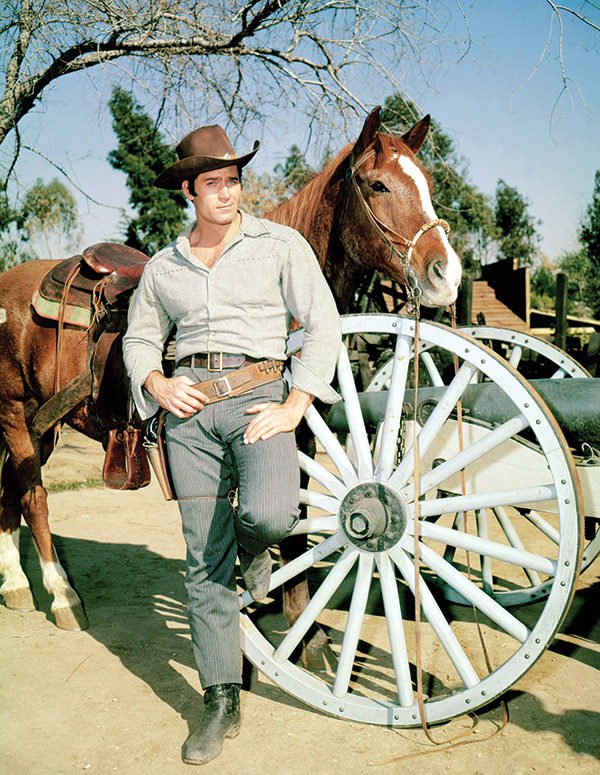

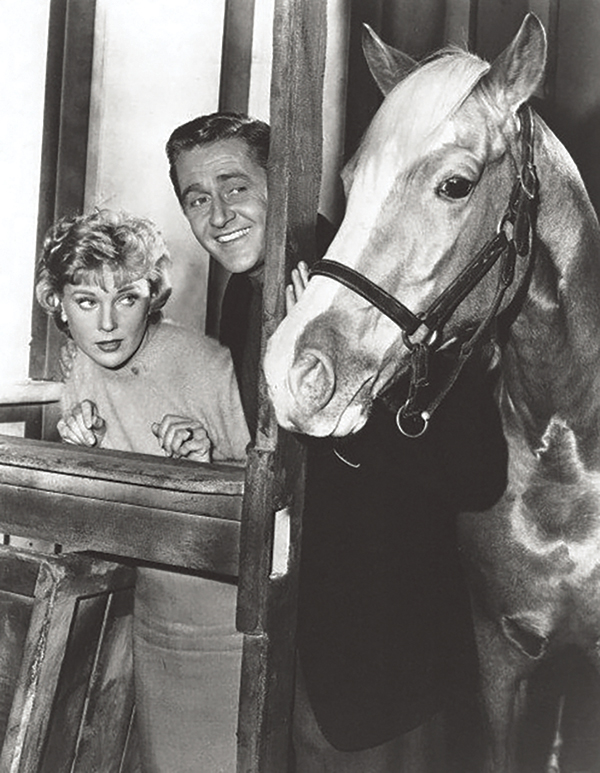

Leading actor Clint Walker played Cheyenne Brodie in the ABC/Warner Bros. hit Western series, Cheyenne, from 1955 to 1963. It was the first hour-long Western and the first hour-long dramatic series of any kind with continuing characters to last more than one season.

Clint Walker, who played Cheyenne Brodie in the Western series, Cheyenne, with his 16-hand co-star, Brandy. Photo: Alamy/Everett Collection Inc.

Given Walker’s imposing frame – he was six feet, six inches tall – he was matched with a 16-hand sorrel horse with a blaze, named Brandy. The mount made his debut in the Season Two episode, The Long Winter, and remained Walker’s horse for the rest of the series. So attached was Walker to Brandy that he also did three features with him including Fort Dobbs (1958), Yellowstone Kelly (1959) and Gold of the Seven Saints (1961). In later interviews, Walker said that the horse never once let him down.

Dependable horses didn’t necessarily go hand in hand with dependable production people, who sometimes did not fully understand the hazards faced by stunt people and doubles — but fortunately, the wranglers in charge of the horses did.

“When Casting called you, they told you what you would be expected to do,” says Crawford-Cantarini. “I did not do any horse falls, but could pretty much do anything else they asked me to do with my horse. But I never had much time to prepare for anything. They told you what they wanted. You knew the wranglers had the right horse for you, and away you went. The young horse I jumped on MGM’s Interrupted Melody (1954) had never seen a jump before, but he was well-trained and was willing to do anything I asked him to do.”

In that movie, the story of the great opera singer Marjorie Lawrence who battled polio, Crawford-Cantarini doubled for Eleanor Parker (to whom she bore a startling resemblance) and she got the job based on her ability to mount a bareback horse in two seconds. The scene was the recreated fire sequence in Wagner’s Gotterdammerung, and her horse, Ski, had to rear in front of the smoke and flames and then leap into the extraordinary fire created by the special effects team at MGM. Martha had to make the required operatic gesture, turn and swing onto Ski to a musical cue in a two-second time frame.

“They played the music and exactly one beat before the exact moment in the music when I had to mount, Ski braced himself with his left foot. He actually listened to the opera music anticipating the action!”

A testament to the immense popularity of Westerns, the American Western television series, Bonanza, ran from 1959 to 1973 as NBC’s longest-running Western, lasting 14 seasons and 431 episodes. Set in the 1860s, it focussed on the wealthy Cartwright family and their 1000 square mile Ponderosa Ranch located near Virginia City, Nevada. Main cast of Bonanza (L-R) Dan Blocker (Hoss), Michael Landon (Little Joe), Lorne Greene (Ben), Pernell Roberts (Adam). Photo: Wikipedia

In MGM’s The Sheepman (1958), in which she doubled Shirley MacLaine, she was supposed to frighten lead actor Glen Ford by almost running over him with her horse.

“Glen Ford was to walk onto the road and into the path of the horse and buggy that were running into town. They appeared as if they would run over him. Glen was apprehensive about that and wouldn’t come any closer to his mark. After doing the shot many times, I decided I would tear into the scene and aim Ski directly at him. I knew Ski wouldn’t really run over him. But it startled Glen. He threw his hands up and the director yelled, ‘That’s a print!’”

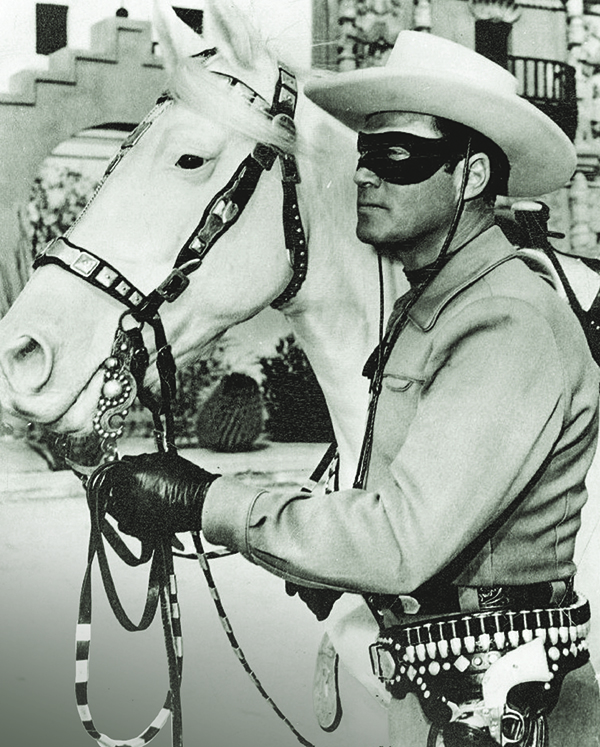

But even 20 years before The Sheepman, horses were galloping their way into people’s hearts. According to an article by David H. Shayt in the Smithsonian Magazine (October 2001), in the early 1930s George Trendle, co-owner of Detroit radio station WXYZ, developed a radio hero who was a blend of Zorro, Robin Hood, and the Texas Rangers. He would become the legendary masked Lone Ranger and he chased bad guys across the radio waves from 1933 to 1954. But in 1937, Republic Pictures began producing The Lone Ranger short films in episodic format. That sent them looking for a horse.

Enter Ace Hudkins, one of the early horse suppliers, stunt workers, and wranglers in the movie industry. An acclaimed boxer in his early years, with his brothers he bought a stable and a string of horses in the late 1930s. They set up shop in Taluca Lake, a neighbourhood in Los Angeles, and rented the horses, along with wagons and cowboy paraphernalia, to production companies. In 1938, Republic came to the stables in search of a horse for the Lone Ranger, and Hudkins rented them Hi Yo Silver, a white gelding that would hoofprint his place in history as “a fiery horse with a speed of light, a cloud of dust, and a hearty ‘Hi Yo Silver!’”

Above: Hi Yo Silver! Clayton Moore as the Lone Ranger, with Silver, from a personal appearance booking at Wakefield Massachusetts.

Below: Clayton Moore as the Lone Ranger riding Silver, and Jay Silverheels as Tonto riding Scout. Photos: Wikimedia

That name became the Lone Ranger’s trademark call, not only during those early short films, but during The Lone Ranger television series that debuted on ABC on September 15, 1949, starring Clayton Moore as the legendary masked rider. The final episode aired June 6, 1957.

The Canadian connection to the television series was the character Tonto, the Lone Ranger’s sidekick. Tonto was played by Harold J. Smith, a full-blood Mohawk from Six Nations Reserve near Brantford, Ontario. He later changed his name to the familiar Jay Silverheels.

Among the horses in Hudkins Stables was a striking palomino named Golden Cloud. Hudkins had purchased the horse as a three-year-old from a small San Diego ranch partly owned by Bing Crosby. Golden Cloud, a 15.3 hand Thoroughbred/draft cross, was born July 4, 1934. He was one of Hudkins’ favourite horses and he was ridden by Olivia de Havilland in the Warner Bros., 1938 classic The Adventures of Robin Hood, which also starred Errol Flynn.

According to the website www.IMDb.com, Roy Rogers was cast in the lead role in Republic Pictures Under Western Stars, also released in 1938. Hudkins Stables offered him several of their best horses, but his eye settled on the palomino Golden Cloud. When he tried the horse out, he was amazed at how smoothly Cloud moved and responded to his cues.

“He could turn on a dime and give you some change,” Rogers is quoted as saying of the horse.

One of his colleagues on the film set mentioned how quick on the trigger the horse was. Rogers agreed, renamed Cloud as Trigger and, in 1943, purchased him from the Hudkins Stables for $2,500, which was a fortune in those days. Roy Rogers and Trigger went on to appear in 82 films and 101 episodes of The Roy Rogers Show. They became the best-known Western “couple” on the continent, and Rogers said of his horse that he never let him down and he never fell. Trigger had his own double – Little Trigger – and he had his own fan club with members from around the world. In addition, Rogers had Trigger Jr., his touring horse, for personal appearances in the 1950s and 1960s. All horses were trained to do a wide variety of tricks.

Above: Roy Rogers and Trigger appeared in 82 films and in 101 episodes of The Roy Rogers Show.

Below: Lynne Roberts, Roy Rogers and Trigger in Billy the Kid Returns (1938). Photos: Wikimedia

Trigger won a PATSY Award for his appearance in Hope Enterprises’ Son of Paleface released in 1952, starring Bob Hope, Jane Russell, and Roy Rogers. The PATSY Award was created in 1951 by the Hollywood office of the American Humane Association (AHA). PATSY was an acronym originally for Picture Animal Top Star of the Year, and the first-ever PATSY was hosted by actor (later President) Ronald Reagan. In 1958, the PATSY Award was expanded to include television animal performers, and the Award became Performing Animal Television Star of the Year.

Trigger won a PATSY Award for his appearance in the 1952 film, Son of Paleface, starring Bob Hope, Jane Russell, and Roy Rogers.

The Award originated in honour of performing animals after a horse was killed during the filming of the movie Jesse James starring Tyrone Powers.

During those early decades, the dark side of the movie industry was that horses were often viewed by production companies as commodities. They were expendable. Tripwires were used to get horses to fall, causing lameness, broken legs, and other injuries often resulting in euthanasia.

In the Warner Bros. 1936 production The Charge of the Light Brigade, the battlefield set was lined with tripwires and during the filming of the climactic charge, 125 horses were tripped, of which 25 were killed or had to be euthanized later. Lead actor, Errol Flynn, an accomplished horseman, was outraged at the animal cruelty.

Then came the cliff hanger in 20th Century Fox 1939 production, Jesse James.

The script called for a horse to be ridden off a cliff into a river. The terrified horse was killed and its untimely death led to such outrage and protests that the AHA opened its Western regional office in Hollywood to fight cruelty to animals in film and television.

“When I was working, it was past the time of the tripwires,” says Crawford-Cantarini. “The American Humane Association had a man on the set most of the time as I remember. They were almost overly doing their job — they brought bits in cellophane wrappers, would only let a horse rear eight times, to name a few. This, mind you, was if we were working within the 300-mile limit. Out of that it was not good.”

Crawford-Cantarini describes the 300-mile limit as an agreement between the studios and the AHA, which was in control for all films shot within the 300-mile limit of the studio. Beyond that limit, the AHA was not in control.

She says that many, but not all, of the producers back in the 1950s were unconcerned if an animal died.

“Most of them couldn’t care less if they killed an animal as long as they got the shot. It was really bad. There were always those ego-prone actors who wanted to do it their way, such as [one actor] who snatched his horse by the reins so hard on The Big Country that he broke the horse’s jaw. It had to be euthanized. Thank goodness for the wranglers who had control of the horses. The head wrangler usually had an office at the studio for the filming and, bless them, they saved many a day.”

She says that, when working just for the day, the horses were usually tied to the horse truck and given water on a regular basis. They were all fed early prior to arriving and when they went home. If they were on location, the wrangler went ahead and made arrangements for them.

“They had horses that were just for the stars to ride and they were the ‘cast’ horses. Then they had ones for us to ride to do the doubling on. I never saw a horse that was a problem and that didn’t have a kind eye. The stables that owned the horses, and the wranglers who took care of them, were wonderful. The ramrod [head] wrangler would be given the production script by the studio and he, in turn, would select and acquire the proper horses. He would search for gentle horses for the stars and to be used during the close-ups, and he would search for matching action horses for the doubles to ride. They would often paint a horse to match, giving it a white blaze face, stockings, or to cover existing white markings if need be.”

Yet, despite all the protests and the hard work that the AHA did to monitor animal welfare and abuse, some productions really crossed the line. The making of Partisan Production’s 1980 Western, Heaven’s Gate, was one such film. Claims were made that four horses died and many more injured during a battle scene. It was also claimed that one horse was blown up by dynamite and that there were abuses to livestock. It was alleged that chickens died in cockfights and cattle were killed so their guts could double for those of human actors. The alleged abuses led to boycotts of the film by humane societies across the United States. The outrage led to AHA’s presence on more film sets to monitor safe care of performing animals. That step launched the coveted “No Animals Were Harmed”® end-credit certification for all productions that met its rigorous standard of care for animal actors.

Today, the AHA works with production personnel and trainers during the pre-production stage through on-set filming, to monitor their Guidelines for the Safe Use of Animals in Filmed Media. According to its website, www.americanhumane.org, it currently monitors 70 percent of known animal action in film and television, which accounts for approximately 2,000 productions annually.

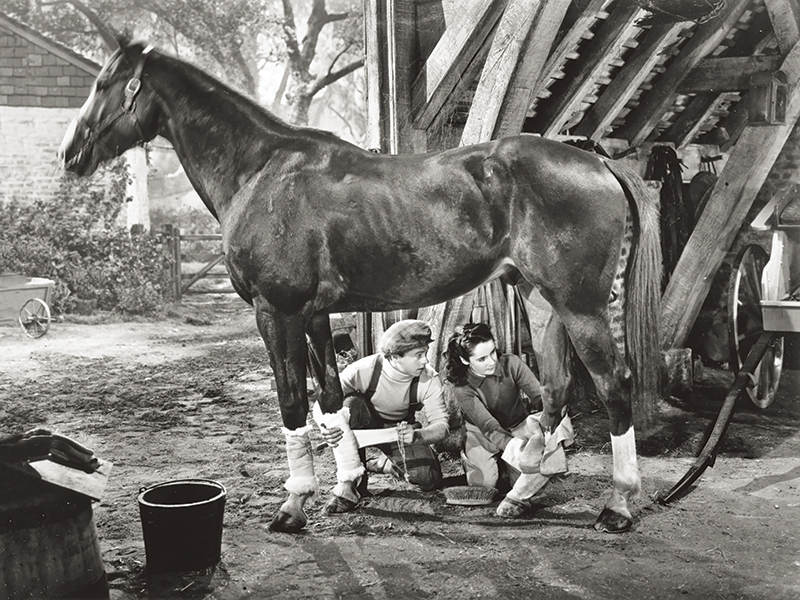

By the 1940s, some big names were starting to appear, among them 12-year-old Elizabeth Taylor who took the leading role in MGM’s 1944 National Velvet. Based on the novel of the same name by Enid Bagnold, the plot revolved around Velvet Brown winning a spirited gelding in a raffle and training him to race in the Grand National steeplechase. Helping her was Mi Taylor (Mickey Rooney). Playing the gelding that Velvet named ‘The Pie’ was King Charles, a grandson of legendary Man o’ War (1917-1947), considered one of the greatest Thoroughbred racehorses of all time. Man o’ War won 20 of his 21 races, was American Horse of the Year in 1920 and Leading Sire in North America in 1926. And among King Charles’ lofty relatives was his first cousin, champion Thoroughbred Seabiscuit.

Mickey Rooney, Elizabeth Taylor and The Pie in National Velvet. Photo: Wikimedia

Taylor fell in love with King Charles and spent every day riding and caring for him, bonding together in preparation for her role in the movie. King Charles was reported to be a bit aggressive with his handlers, but never with Taylor. During the filming of the race scene, Taylor took a nasty fall and broke her back. Although she recovered quickly, the injury would come back to greatly haunt her later in life. When filming was over, MGM gifted the horse to Taylor, and she and King Charles remained together until his death.

The combination of children and horses remained immensely popular. In the 1956-1957 television season, 20th Century Fox produced My Friend Flicka, a 39-episode series about the adventures of a boy, Ken McLaughlin, played by Toronto-born Johnny Washbrook, and his horse Flicka, played by Wahana, a registered Arabian mare foaled on June 13, 1950. The name Flicka means “little girl” in Swedish. The first episodes were in black-and-white, but production quickly shifted to colour. Even though the series only had one production season, the 39 episodes enjoyed many reruns over the years on other networks.

Gene Evans, Johnny Washbrook, Flicka, and Anita Louise from My Friend Flicka, 1957. Photo: Wikimedia

Training Flicka and her double, Goldie, was legendary horse trainer Les Hilton, who lived in North Hollywood and whose backyard was a shedrow of horse stalls, with a barn for training. He also used Ace Hudkins’ facilities for further training.

“I think Les Hilton was the best horseman,” says Crawford-Cantarini. “He was the only one I worked with on set. He trained Flicka, Mr. Ed, and Francis the Talking Mule. My horse, Jim, doubled Flicka in the free-jumping scenes.”

Francis the Talking Mule was based on a book by David Stern about a military man, Peter Sterling, who meets Francis, a mule experienced in military ways — who could talk. Seven films were produced in the 1950s and what made them appealing was that only Peter could hear Francis’ comments.

Playing Francis was a female mule called Molly and she was trained by Les Hilton. To make her appear to speak, Hilton used a piece of nylon thread fed into her mouth which, when gently tugged, caused her to move her lips to remove it. Providing Francis’ voice was character voice actor, Chill Wills. Arthur Lubin, producer of the Francis movies, went on to produce Mr. Ed, and the same techniques for getting Molly to appear to speak were used on Mr. Ed.

The main cast of the television program Mister Ed (L-R) Connie Hines as Carole Post, Alan Young as Wilbur Post, and Mr. Ed. Photo: Wikimedia

The black-and-white television series, Mr. Ed, ran on CBS from 1961 to 1966 and featured a gelding played by Bamboo Harvester, a Saddlebred/Arabian cross. His stablemate, a Quarter Horse named Pumpkin, was his double. As the series progressed, Mr. Ed learned to move his mouth on cue when trainer Les Hilton touched his hoof. The series followed similar plot lines to the Francis film series in which Mr. Ed only talked to one person, his owner Wilbur Post.

The beauty and remarkable achievements of celebrated horses became the focus of heartwarming features. And if ever there was a horse movie that really exploded on the screen, it had to be the 1979 American Zoetrope’s The Black Stallion, distributed by United Artists. No one can forget those magical shots of Alec Ramsey (played by Kelly Reno) shipwrecked alone on an island with the beautiful black stallion, and their slow deliberate steps to get to know each other before being rescued. Filmed in Sardinia, Italy (for the beach and island scenes), Oregon and Ontario, the story followed their rescue and all the twists and turns that led to the horse race of the year and the entry of the mysterious black horse.

The Black Stallion (1979) tells the story of young Alec who, while traveling with his father, becomes captivated by a mysterious Arabian stallion that is brought on board and stabled in the ship he is sailing on. When the ship tragically sinks both he and the horse survive, only to be stranded on a deserted island. Alec befriends the horse, so when finally rescued both return to his home where they soon meet Henry Dailey, a once successful trainer. Together they begin training The Black to race against the fastest horses in the world. Photo: Alamy/Entertainment Pictures

Playing the Black Stallion was the Arabian stallion Cass Ole, owned by Francesca Cuello in San Antonio, Texas. But Cass Ole had doubles too, in particular Fae-Jur, an Arabian stallion chosen for his liveliness, as well as two other horses that were used as doubles for specific action scenes. The producers felt that no one horse could have all the range of expression and attitude necessary in the film to transform the stallion from the animal on the beach to companion to racehorse.

All four horses went into training for 11 weeks prior to the start of principal photography, and Kelly Reno joined with them for several weeks to establish his rapport with Cass Ole, his equine co-star. At the end of training, they could all respond to visual and vocal cues such as coming when called, being sent away, backing up, and laying their heads down. They learned to pin their ears to show anger, rear, paw the ground, stomp on a fake snake, nod their heads, and lie down.

The film was so successful that a sequel The Black Stallion Returns was produced in 1983, and the prequel The Young Black Stallion was released in 2004, telling the story of The Black in his early days with a young girl named Neera, who named the horse Shetan.

In the prequel, 40 Arabian horses were used as well as 10 camels. All the horses were picked by Australian horse trainer Heath Harris and came from a breeding farm in South Africa. Location filming was done in Morocco and two members of the Animal Anti-Cruelty League were on set all the time to ensure the well-being of the horses and the other animals. The story included a grueling endurance race, and, despite the challenges and the extreme heat, no animal was injured or placed under undue stress.

Film production using horses came to Alberta in 1970 with Cinema Center Films’ Little Big Man. Horses were provided by John Scott, owner of John Scott Productions & Motion Picture Animals. His ranch is based in Longview and, in almost 50 years, he has provided services as wrangler, stunt coordinator, and location scout for over 150 film and television productions, as well as numerous commercials.

Jackie Chan and a horse in Shanghai Noon, one of many films for which Alberta’s John Scott Productions & Motion Picture Animals provided head wrangler and stunt services. Photo: Alamy/Touchstone/AF Archive

“The business came, and the budgets were kind of wide open,” says Scott. “It wasn’t tight when we did Little Big Man. The money was there, and they kept shooting until the picture was done. I keep over 100 horses and use a lot of Quarter Horses, but what I really like is a Quarter Horse/Belgian cross. They have to stand for long periods in the day, and the Belgians and Percherons stand that much better. They must have the right temperament and attitude for specialized training for stunts like rearing, lying down, falling. Now they are using drones flying overhead so you have to train the horses to get used to them.”

He has worked as wrangler/stunt coordinator on five Oscar winning films including The Revenant (2015), Lord of the Rings (New Zealand, 2001), Legends of the Fall (1993), Unforgiven (1992), Days of Heaven (1976) and Emmy winning film Bury my Heart at Wounded Knee (2007).

Above: In the blockbuster Lord of the Rings series of three fantasy adventures films, horses were portrayed as the primary working and fighting animals in Middle-earth. Many spectacular horse scenes added to the series’ appeal. Pictured are Viggo Mortensen, Orlando Bloom, and Sir Ian McKellen in The Two Towers, the second instalment in the trilogy. The angelic white horse who was the primary equine actor to play Gandalf’s mythical steed Shadowfax was Blanco, an Andalusian gelding. Photo: Alamy/Allstar Picture Library

Below: The terrifying ringwraiths and their armoured black horses chase after Arwen and the gravely injured Frodo in The Fellowship of the Ring, the first instalment in the Lord of the Rings trilogy. Photo: Alamy/AF Archive

Of all the films he has worked on, Legends of the Fall starring Brad Pitt, Anthony Hopkins, and Aidan Quinn stands out.

“It was my most memorable show,” says Scott. “Brad Pitt had never ridden before and, on that picture, we had him on seven different horses. He rode really well. I spent four years with the director [Edward Zwick] helping him get the picture made and we finally got it done here in Alberta.”

The film won an Oscar for best cinematography.

Of all the films he worked on, John Scott says Legends of the Fall starring Brad Pitt stands out as the most memorable. “Brad Pitt had never ridden before and, on that picture, we had him on seven different horses. He rode really well,” says Scott. Photo: Alamy/Album

Scott also provides horses for the CBC series Heartland and, like many shows, it comes with its challenges.

“It can be a challenge because there is always an adverse horse situation,” he says. “The script may call for a horse that won’t load in a trailer. Our horses are well trained and load into trailers really easily. That means you’ve got to gimmick the horse and have someone with an air hose under the trailer or with an umbrella inside. Trouble is, you are ruining your initial training on the horses, then you have to spend two or three weeks to bring them back.”

He emphasizes how important it is to have reliable horses all the time.

“You’ve got to have horses that actors can work around, ones they can ride and the ones that can act up [as the script calls] so it’s always double horses on that series.”

Hidalgo is a biographical Western movie based on the legend of American distance rider Frank Hopkins (Viggo Mortensen) and his Mustang, Hidalgo. A former dispatch rider for the US cavalry and once billed as the greatest rider the West had ever known, Hopkins is invited by a wealthy Arabian sheik to race his horse in Arabia against Bedouins riding pure-blooded Arabian horses in a gruelling 3,000-mile survival race across the desert in 1891. Photo: Alamy/AF Archive

Heartland is now in its 13th season and Scott says the show could go to 15 seasons. He currently has about 15 horses on the show but, in addition, his crew brings in outside horses for jumping, liberty, or trick riding.

“They come in, depending on what the script calls for,” he says. “Every episode is different. We have a week to train a horse to do what the script writers write. We had a horse for a guy in a wheelchair. He had to get up from the wheelchair, transfer onto the horse, then ride in a special saddle.”

Above: Amy Fleming (Amber Marshall) and Jack Bartlett (Shawn Johnston) of CBC’s hit series, Heartland. The show, now in its 13th season, follows sisters Amy and Lou Fleming, their grandfather Jack Bartlett, and Ty Borden through the highs and lows of life at the ranch. Filmed primarily on location in and around High River, Alberta, it is the longest-running one-hour scripted drama in Canadian television history.

Below: Alberta’s John Scott Productions & Motion Picture Animals provides about 15 horses for Heartland, and also brings in outside horses for things like jumping, liberty, or trick riding. Depending on the script, they have a week to train a horse to do what the writers call for, says Scott. Photos courtesy of CBC.

In 2003, Universal Studios (along with others) produced Seabiscuit, the story of the celebrated racehorse foaled in 1933 out of Swing On. His sire was Hard Tack, a colt of Man o’ War, Seabiscuit’s grandsire. Seabiscuit was named after his sire since hard tack, or “sea biscuit” was, back then, the name of a kind of cracker eaten by sailors. He was only about 15.2 hands and failed to win his first 17 races. But, in 1938, the stallion went on to beat the 1937 Triple-Crown winner, War Admiral, by four lengths in a special two-horse race at Pimlico Race Course in Baltimore, Maryland that stopped the nation in its tracks.

Tobey Maguire riding Seabiscuit in the story of the undersized racehorse in the United States who began his career with 17 consecutive losses, before becoming one of the most successful race horses in history. His incredible victories made him a household name and a beloved symbol of hope to downtrodden Americans during the Great Depression. Photo: Alamy/Sportsphoto/Universal Pictures

The film about this Racing Hall of Fame horse was an adaptation of the best-selling 2001 book by Laura Hillenbrand, and was nominated for seven Academy Awards including Best Picture.

Playing the undersized, scrappy Seabiscuit was 1 Two Step Too, one of 10 horses that portrayed the racehorse’s life on and off the track. Each horse was chosen for very specific shots, but it was 1 Two Step Too that was featured in the close-ups and racing scene highlights. The horse lived at Kentucky Horse Park in Lexington and was, essentially, the main attraction. But, in 2004, 1 Two Step Too had surgery for a rare nasal cavity tumour. It kept re-growing and the following year he was euthanized at age 11.

Above: Horses were integral to many of the dramatic scenes in the 2000 epic historical drama, Gladiator. Early in the film, General Maximus leads his troops against the Teutonic army of Germania in the name of the Roman Empire. This bloody battle is fought on horseback, with the Roman mascot, a wolf, fighting at his master’s side. These scenes, filmed in Allice Holt Forest in Surrey, used approximately 100 horses including trained falling horses. Two dogs, Belgian Shepherds, doubled as the wolf and were conditioned to run with the horses.

Below: Some of the Roman cavalry in the opening battle of Gladiator were real soldiers. The movie employed 20 members of the British Army’s King’s Troop, Royal Horse Artillery. King’s Troop’s horse-drawn ceremonial guns sometimes have to travel at high speed despite each weighing over a tonne and having no brakes, so the soldiers are required to be very skilled horse-riders. Photos: Alamy/Lifestyle Pictures

In 2010, Walt Disney Pictures released Secretariat, the story of the legendary racehorse who in 1973 was the first Triple Crown winner in 25 years. His victory in the Belmont Stakes, which he won by 31 lengths, set a track record that stands to this day. He was perfectly conformed and, in addition, carried the large heart gene, giving him his oversize chest. He went on to clean up on all the racing awards, and was the Leading Broodmare Sire in North America in 1992. When he died in 1989 at Claiborne Farm, Paris, Kentucky from laminitis at age 19, his story was begging to be told.

His owners were Penny and Christopher Chenery who owned Meadow Stable in Caroline County, Virginia, where Secretariat was foaled in 1970. Penny was an actress and producer, and Secretariat’s story in the movie was largely based on William Nack’s 1975 book Secretariat: The Making of a Champion.

The movie, Secretariat, chronicles the life of Penny Chenery (portrayed by Diane Lane), and how, against all odds, she navigated the male-dominated racing business and made history by winning the 1973 Triple Crown with her phenomenal Thoroughbred stallion. Photo: Alamy/Entertainment Pictures

To find the horse to represent Secretariat, Chenery made the selection from a look-alike contest in Kentucky. The principal horse ended up being Trolley Boy, who looked the most like Secretariat. In fact, Trolley Boy was Secretariat’s great-great-grandson.

In total, five horses were selected to play the part, four Thoroughbreds and a Quarter Horse, each needing some form of cosmetics to replicate the racehorse’s three white socks, strip, and star. One of them, Longshot Max, was considered the most close-up friendly. And Longshot’s bloodlines included Secretariat’s sire, Bold Ruler, and his damsire, Princequillo. The equine stars were definitely in the family tree.

Movies featuring horses are enduringly popular, such as Dreamworks Animation Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron (2002), with Spirit’s thoughts narrated by Matt Damon; Touchstone Pictures Hidalgo (2004), the story of a long distance race; Tollin/Robbins Productions Dreamer (2005), inspired by the true story of the injured Thoroughbred, Mariah’s Storm, that returns to racing; and Cedar Creek Productions Buck (2011), a documentary about the real life horse whisperer, Buck Brannaman, who was the lead equine consultant on Robert Redford’s 1998 film, The Horse Whisperer.

In December 2011, Dreamworks Pictures (and others) produced War Horse directed by Steven Spielberg. The film was based on the book War Horse by Michael Morpurgo, and paid tribute to the over eight million horses on all enemy sides that died tragically in World War I. The story follows Joey, a farm horse raised by Albert Narracott, who teaches him to come when he imitates an owl’s call. But Joey is deployed to the horrors of the front lines during World War I, and Albert eventually enlists. The two are reunited at the end of the war when Joey hears Albert’s haunting owl call.

Filming of War Horse took place in England and 14 horses portrayed Joey, while four horses played Topthorn, Joey’s equine friend. In some scenes, especially the “No Man’s Land” sequence, an animatronic horse was used in places, and the barbed wire Joey was trapped in was rubber prop wire.

Spielberg’s War Horse centres around the powerful friendship between a boy, Albert, and his horse, Joey. Sadly, Albert and Joey are parted with the outbreak of World War I, when Joey is sold to a captain in the British army. Bottom left: A panicked Joey gallops through No Man’s Land in this horrific but memorable scene. Photos courtesy of Walt Disney Motion Pictures Canada

To ensure the safety of the horses, an animal safety representative with the AHA oversaw hundreds of horses during production. One cavalry charge involved 130 mounted extras. Critical eyes were what Spielberg wanted and what earned the film the coveted “No Animals Were Harmed” AHA seal of approval.

He later praised the equine team, commenting that horse master Bobby Loygren and his team literally performed miracles with the horses. Their safety was paramount, and he appreciated the fact that the AHA representative was there for every single shot. He gave them full power to pull the plug if any of the horses were not up to the challenges or there was danger of injury. They oversaw all the action and stunts the horses performed, starting with the rehearsals where each action scene moved in slow motion, one step at a time, to assess its safety level for when it would be filmed.

In England, The Devil’s Horsemen is the leading film-industry horse supplier and provides not only horses but carriages, tack, riders, and horse masters to international film and television producers. Their clients include Disney, Warner Bros., Universal Pictures, HBO, Netflix, and Fox Broadcasting. Based in the ancient village of Mursley in Buckinghamshire, they have over 100 highly trained horses, as well as over 600 horse-drawn vehicles, tack, saddlery, armour, and horse dressings for every period and genre in history, on a 120-acre property that includes indoor and outdoor training facilities.

The company was started in the early 1970s by Gerard Naprous, who came to England from Paris, France. He bought two horses called Snoopy and Topaz, did small events, and added more horses as his shows became bigger. Two children, Daniel and Camilla, came along and The Devil’s Horsemen became a family affair, expanding from performance shows to providing horses for movie and television sets, and setting a whole new level of expertise in choreographing epic battle scenes with large teams of action riders. Those high-speed sequences leave no room for error.

“The horses become different roles – ride, drive, action,” says Camilla Naprous. “They settle in and find their place. Some horses work sporadically six months of the year. There are no star horses. It doesn’t matter if they are carrying an A-list star or pulling a carriage.”

The horses of The Devil’s Horsemen stable have carried such A-list stars as Emma Stone, Michael Fassbender, Chris Pine, Angelina Jolie, Christian Bale, Scarlett Johansson, and Madonna.

Their horses are broken in at three years of age and, by five, they start working their way up the ranks. Naprous watches how they progress, believing in giving them time to grow and develop.

“In 2017 we did 26 different productions,” she says.

The company provided horses for The Crown for Netflix; Wonder Woman when filming in Tenerif and Fuerteventura, the second largest of Spain’s Canary Islands; and all eight seasons of Game of Thrones.

“It was amazing to be attached to a project for so long,” says Naprous. “Eight years of my life. Usually, you do a project and it’s done. But to be involved with a project for eight years, you have to constantly evolve. The viewer wants to see more, but how do you hold back and not show everything straight away? I really had to thank the writers, David Benioff and Dan Weiss, for giving me the opportunity to create things. They came to me years ago and said if there is anything you feel like you want to put on the screen that hasn’t been done before, please bring it to us. We’ll write it into the script. It was so lovely to be given that opportunity and have someone put that trust in you. It was a wonderful experience and one I’ll never get back again. You’ll have other experiences, but I’ll never recreate what I had in those eight years. It was so family-orientated, and everyone had each other’s backs.”

Leading film-industry horse supplier, The Devil’s Horsemen, provided horses for all eight seasons of Game of Thrones. The horses performed many different roles, from carrying A-list actors to pulling a carriage. “They settle in and find their place.” Photo: Alamy/Moviestore Collection Ltd.

The Game of Thrones’ Battle of the Bastards used 100 horses. “We shot most of it in Belfast, Northern Ireland, then went to Iceland, Croatia, Malta, and Spain.”

For Game of Thrones, Naprous policed the care of their horses herself. When providing animals for other productions with, for instance, Warner Bros. or Disney Productions, she says that the AHA will monitor animal action and care, which Naprous always welcomes.

“I look after my boys and never put them into any line of danger,” she says. “As horse master, I organized the logistics for getting horses across Europe, teaching the actors, and planning the action. My job was to be the voice of the horse.”

She says that, during filming, the expectations of scripts grew, and everyone wanted to reinvent the wheel. But, to her, it was the thrill of telling the rich story of the horse.

“One movie we are in a medieval world, then it’s a fantasy world, then the 1960s, 1930s, World War I. Or go back to the 15th and 16th century horsemanship. I wanted to respect that. It’s amazing how much horses are involved in our history.”

In 2018, Naprous was inducted into the National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame in Fort Worth, Texas. She was recognized for the spectacular stunt riding sequences, her contribution to choreographed battle scenes, and her dedication to working with producers to bring their vision of a film to life using period-specific horses, carriages, and tack.

Working with horses in film leaves indelible memories.

“My favourite one is a horse too well-trained for the job,” recalls Crawford-Cantarini. “In the film, I was to ride a racing harness horse down the track in front of an empty grandstand, bareback at a full trot. It was a snap to do and a lot of fun. However, they gave me a horse that was retired but, at one time, had really been on the track racing. When I headed him down towards the wire, he was in seventh heaven. He was back doing what he knew he could do. It was a great shot, but when the time came to stop, I could not get him stopped. Those horses, the more you try to stop them, the faster they run! I thought after one lap, oh well. I will wave at the outrider to pick me up. I waved at him and he waved back! He thought being as we were just trotting, it was no problem. It was a half-mile track and after I had made a couple more laps, he finally realized I could not get stopped. I was out of breath but laughing so hard it didn’t matter. What a dear horse he was.”

For Naprous, she sees the horse in life and in film as an artform.

“They have taught me so much, taught me to learn to let go, just be and to trust. The horse has a different kind of communication through body language and movement. We all change through our lives. Same with horses. They have transported us around the world. We should always respect them that way, carry that message on, pass on that knowledge.”

In so many ways, that message continues to be shared and passed on in the echo of hoofbeats across the silver screen.

By Margaret Evans

Provided by HorseJournals.com